As a child in upstate New York, I often roamed the fields and woods behind my house. Like everybody else then, when thirsty I would sip from a stream. Of course, groundwater is contaminated everywhere now, and this simple pleasure is no more.

Far more serious, though, is the contamination of ourselves: by accepting

this kind of pollution as a natural state of affairs, we have become

creatures who foul their nests.

We recognize this as a trade-off of the technological age. But another legacy of that age is the grit to face any challenge. Let us gather our wits then and think about cleaning up. A formidable job: the befoulment has its hot spots--oil spills and industrial corridors, but its worst aspect is invisible because it is finely spread everywhere: in the waters, throughout the atmosphere, across all lands, in our foods, in our mothers milk. This Big Mess is the final and inevitable outcome of Western Man’s deep, long-standing perception of the earth’s resources as just an unlimited supply of raw material for his pleasure, and such pleasures as the principle goal of life. Such a world-outlook is profane, and moves easily into treating people as useful (or useless) materials too.

Success or failure in the cleanup will finally depend on uncovering these destructive attitudes and establishing new ones. Thus we enter the Third Millennium. Without a baseline shift in world-outlook, everything else we might do--recycling bins and clean water acts and all the rest--is symptomatic medicine, self-deceiving, and doomed to a failure awful to contemplate.

We gain perspective on this work by observing societies which have cultivated a respectful and intimate relationship with the elemental world. Native Americans call such societies “Traditional”.

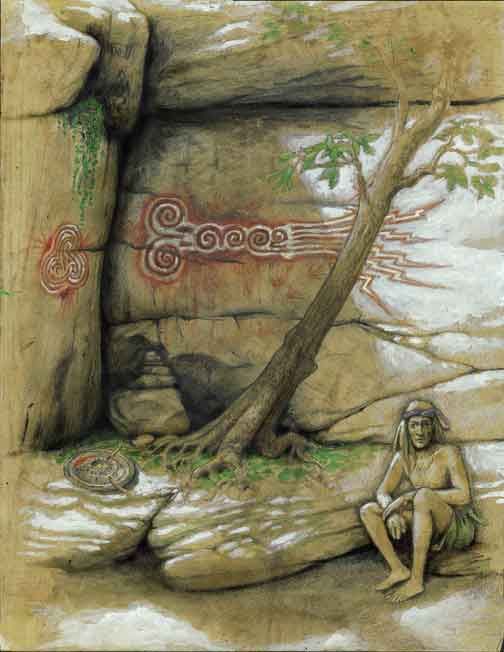

Traditional societies view all of nature as being conscious and partaking of the quality of sacredness. The whole drift of such cultures, particularly in their art, is to nurture and inspire this experience. It is interesting to note that the isolated, decorative “art object” is a relatively modern notion. In the traditional world-view art did not go on the wall; it was the wall...and the room as well. It was a magical power that possessed a space and the people in it. The creation of sacred environments is perhaps our most ancient art tradition, and it holds particular promise today as a means to help shift us into new ways of understanding the world.

Ways of creating sacred space are as varied as sites. A circle of standing stones on a plain; a Tori gate planted to frame an ocean bay at sunrise; delicate paintings telling a mythology across a cave wall; a simple shrine to grace the bubbling-forth of a spring.

Sacred space might even be disguised as an exhibit in a natural history musem, as an art gallery, or even a film theater.

Such places can be large or small. They may address ceremonial gatherings or aid solitary contemplation. If successful, they awaken a sense of the living, sacred nature of the earth--and of a Great Mystery behind the sensible world. These feelings are mystical in nature, but nevertheless accessible to everyone; they are an essential part of what it is to be truly human.

The positive transformative powers of art are rarely drawn upon today. We live in an age which has trapped the artistic impulse for community spirit-healing into what poet Coleman Barks calls “the cage of the personal”--art as a vehicle for individual ego expression and social commentary.

Perhaps that is because of the demands of the real thing. Only when art is the graceful outward gesture of real inner work can it slough off its narcissistic show-off nature. Healing artists must first be pilgrims, priest-shaman-lovers of God and lovers of people. Must first be involved in healing and transforming themselves...and annihilating themselves. Art that emerges from such tended ground is the fragrance of a good life, rather than the justification of a self-centered one, and can aspire to the work of transformation. Or cleanup.

May

such art come to us now, may it find a sweet voice amid

harsh clamor and big messes, may it blossom in an age of

iron!